November 29: Anti-Israel clichés and the 1947 UN vote - analysis

What matters today is that every year on November 29, one of the latest in vogue narratives about 1947 and Israel’s creation is that it was a “settler colonial” enterprise.

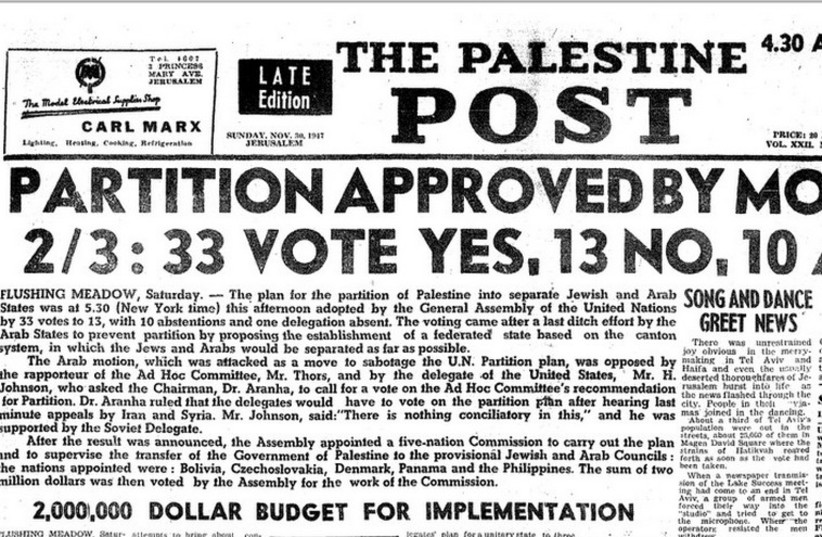

It’s been 75 years since the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 181, setting forth the partition of British Mandate Palestine into two states.

The resolution, supported by 33 countries, opposed by 13, with 10 abstentions, proposed separate Jewish and Arab states. This week commemorates not only the historic vote, but also the expulsion of Jews from other countries in the region.

The Partition Plan, one of several that had been proposed over the years, also had many idiosyncrasies. The proposal foresaw an “international” area in what is now Jerusalem and Bethlehem, including holy sites, in particular the Christian ones.

However, no state in the world has an international zone within it, and certainly no state that was about to be at war internally and with its neighbors was going to be able to peacefully administer such a zone.

Yet the UN, due to the problems of British rule, came up with the idea anyway. The UN plan also spliced the landscape, making both future states practically impossible to govern because they were not contiguous. This line of thought argues that the whole plan was doomed and created as such.

There are many narratives about 1947 and its aftermath.

What matters today is that every year on November 29 – and followed up with Independence Day – one of the latest in vogue narratives about 1947 and Israel’s creation is that it was a “settler colonial” enterprise. This argument is a descendant of the anti-Israel rhetoric of the 1970s and the assertion that “Zionism is racism” as well as the argument that gained wind in the 1990s slandering Israel as an “apartheid” state.The overall goal in these arguments is to portray Israel as a “colony,” to situate it in the colonial period. This was popular in the 1970s because critics believed that Israel could be dismantled in a similar manner to France’s role in Algeria.

For these voices and their intellectual descendants the story is simple: the Palestinians will be encouraged to “resist” through “armed struggle” until Israel’s leaders give up, the way the leadership of apartheid South Africa did in the 1990s, and then there will be “one state.”

The argument is also predicated on support for far-right Palestinian nationalist rhetoric, as well as the ethnic-cleansing of the Jewish population in Israel and “right of return” where Jewish areas are dismantled and “returned” to Palestinians. The whole trend of the argument is rooted in the ideas of the 1970s that glorified “armed struggle” as a means to an end.

The year 2022 is not the 1970s. The Jewish population of Israel has grown significantly and Israel has become much more powerful than it was. It no longer faces a Soviet-armed Egyptian army. Instead, Egypt, Jordan and many other countries have normalized ties. Iran is the main opponent today.

Yet this shift in power and population hasn’t changed the anti-Israel rhetoric. Instead, the anti-Israel framework of 1947 continues to be rooted in a mix of old notions of nationalism blended with more recent concepts of ethnocracy and indigenous rights.

The argument that Palestinians are the “indigenous” people in the region presents many questions about other areas in the Middle East. Who is “indigenous” to the region? How can Jewish people be “settler colonials” when they are from the Middle East.

This is no small matter. The argument that Israel is a “settler” state similar to the creation of Australia or America ignores history. Although many of the members of the First or Second Aliyah of Jewish immigrants to Israel who came before the creation of the state were from Europe, this doesn’t change Jewish history.

Some came to Israel from Europe but many came from neighboring states, while a few were from ancient Jewish families that had never left the land, and some had been in the land for seven or eight generations. Many came from Yemen, the Kurdish region of Iraq, or Lebanon and Syria.

The argument that areas of the Middle East naturally should be divided into “indigenous” states runs into a problem: which areas are “indigenous” and to which group? Do those who argue for “indigenous” rights suggest that Turkey be divided into areas for Armenians and Greeks, populations that were forced out of the country when modern Turkey was created? When anti-Israel voices suggest that “self-determination” is the right of the Palestinians, do they hold the same for the Jews?

The overall problem with the “indigenous” and “self-determination” argument is that it is rooted in ideas of nationalism and irredentism. Not every country can be easily divided into whatever groups lived in whichever places, whether in 1947 or 1840 or 1700.

The thing is that this proposition is not made to other countries in the world.

The 1947 “indigenous” argument opens other disputes about who owned what part of the land. In this reading of history some argue that because Jews only owned land in some areas, that the country should have been divided based on who owned what. But this proposal is bizarre.

Land ownership is often historically based on discrimination, class and racist or religious decisions. For instance, in some places, minorities couldn’t even own land. If one chooses to divide a country based on land ownership in the 1940s they’d run into a lot of problems applying this same idea to the Balkans, for instance.

Lastly, the anti-Israel clichés that are dredged up every November tend to set their sights on the population differences in British Mandate Palestine. They argue that since Jews were a minority of the population, therefore they should have received less in the UN vote.

This population analysis is discriminatory against Jewish migrants. It is ironic that many of the anti-Israel voices who depict Jewish migrants as colonial settlers also tend to support migrant rights today in the West.

In short, they argue that Jewish immigrants, even undocumented ones, deserved fewer rights in Palestine in 1947, that they were “settlers,” but this same racist terminology would never be used against immigrants in Europe or the US. Yet when it comes to discussions about the history of Israel, Jewish migrants are portrayed as an unacceptable “other” precisely because some were migrants.

Undocumented migrants to a British-controlled area in the Middle East are not “settlers.” Therefore the anti-Israel argument perpetuates antisemitic and racist stereotypes by trying to “other” the Jewish migrants and portray them as rootless. It also suffers from a nationalist problem, by depicting only one group as inherently connected to a landscape.

Israel holds an annual memorial day for Jewish refugees expelled from Arab countries and Iran. It is important to recall that the anti-Israel rhetoric regarding 1947 tends to also ignore or even support ethnic-cleansing of Jews from the region.

That means that the “indigenous” discussion never seems to provide rights for those Jews who were from numerous countries in the region. Most of these countries were modern creations, meaning Jewish life in what is today Iraq long predates “Iraq.”

Those people had as much right to move where they wanted in the region as any group, because they were indigenous to the region. They can’t be “settlers” of areas like Tel Aviv, anymore than they were “settlers” when they lived in Fallujah or Beirut. Nevertheless, every year conjures up these portrayals and fallacies.