Did Esperanto answer the ‘Jewish Question’?

Here's how Jewish was the international tongue that never quite made it.

Sub la sankta signo de espero

Kolektiĝas pacaj batalantoj,

Kaj rapide kreskos la afero

Per laboro de la esperantoj.

Under the sacred sign of hope

Gather the peaceful warriors,

And rapidly the cause will grow

By the labor of the hopeful.

(L.L. Zamenhof, “La Espero”, the hymn of the Esperanto movement; third stanza)

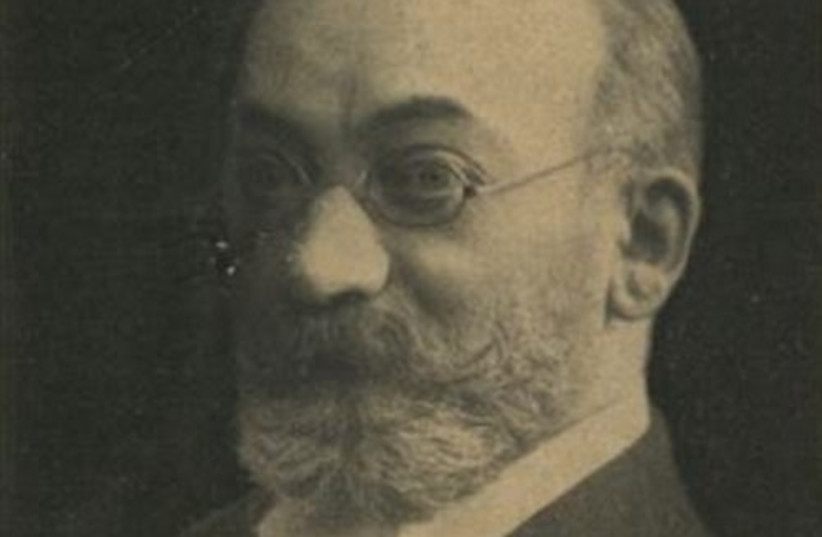

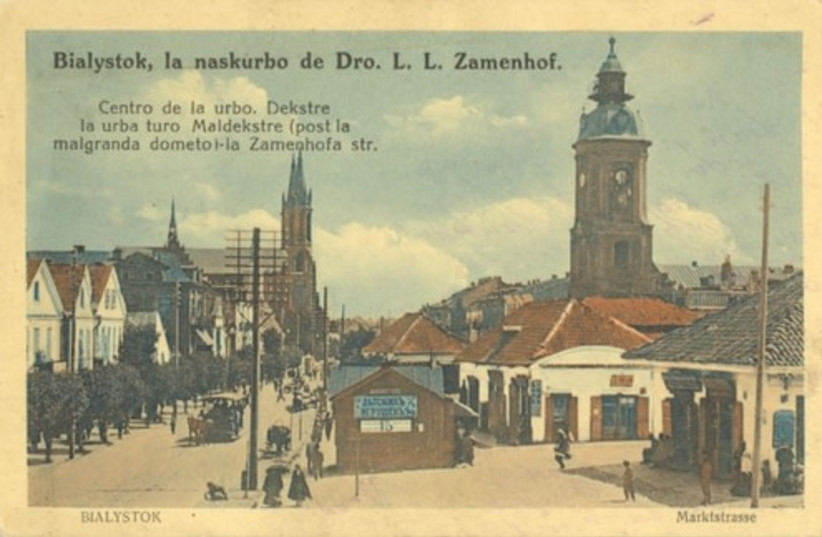

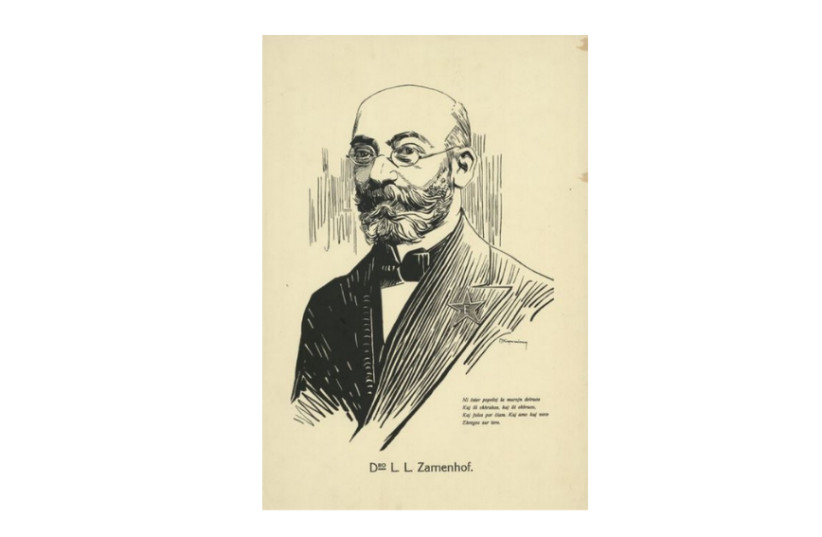

Leyzer (Eliezer) Levi Zamenhof was born in 1859 into a Jewish family in Belostok, a provincial city in the Russian Empire, now Bialystok, Poland. Roughly two-thirds of its inhabitants were Jews. Most of the rest were Poles, Ukrainians, Belorussians, Russians, and Germans. Like many other Jews in the Tsarist Pale of Settlement, the Zamenhofs lived in a multilingual environment. His educated, secularist family spoke Russian at home, but were also intimately familiar with Yiddish, the language that most Ashkenazi Jews spoke on a daily basis – it was, according to one turn-of-the-century statistic, the native tongue of 96% of the Jews in the Russian Empire. The men of the family were also literate in Hebrew and Aramaic, the sacred tongues of the Bible, of prayer, and of Talmudic study.

Sympathetic in his youth to Zionism, in 1882 Leyzer opened a local Warsaw chapter of Ḥovevei Tsiyyon (“Lovers of Zion”) in the wake of the pogroms that swept the Russian Empire. He even met his future wife, Klara Silbernik, at a clandestine meeting of the group. Though in his later years Zamenhof ceased to actively champion Zionism, he never actively opposed it. Rather, like many other European Jews in the years before the unimaginable horrors of Nazism, he thought quite reasonably that life in the European Diaspora, though very challenging, was ultimately viable. Europe was then the center of the world’s progress in science, in culture and learning, and in political reform; and the connection to that continent of the Jewish people, so deeply rooted and so actively involved in and committed to all the facets of its civilization, was surely so vital as to be irrevocable.

Universal and Jewish questions

By the late 19th century, which we now look back to as an age of optimism, political activism and the belief in social and ethical progress were commonplace in the Jewish community. What may seem particularly strange or even absurd to many now, though, is the attachment of ideas precisely about language to schemes for social progress. Many polyglot idealists in the 19th century proposed that an invented language shared by people across borders would be the key factor in the promotion of other ideals of social reform and international peace. Like the belief most Jews still held of a viable Diaspora, this conviction was not at all unusual for the time, and it seemed eminently practical as well. If only people could understand each other and not believe their own native language to be intrinsically superior to that of others, the line of reasoning went, reason would triumph over enmity; fraternity, over chauvinism. The idea that a common language resolves differences seems hopelessly naïve now: one can understand one’s fellow perfectly and still despise him or even want to kill him.

Given the precarious predicament of the Jews, his plans naturally addressed the “Jewish Question”. Zamenhof, a Jew who loved his people, worried about its future and was even sympathetic to Zionism. Yet he was not a nationalist per se, as he stressed the apolitical character of his aspirations, while emphasizing a commitment to ideals of human equality and social justice that transcended partisan politics. Even though Zamenhof saw himself as soaring over the roadblocks, customs houses, and border fences that divide states, and although Esperanto has no earthly locus other than where a speaker of it hangs his hat, the ideas that inform Esperanto still do have a precise location on the intellectual map of Eastern European Jewry of the period. “Esperantoland” on our imagined chart of the intellect is a left-leaning clime situated close to the Bundist and Socialist districts.

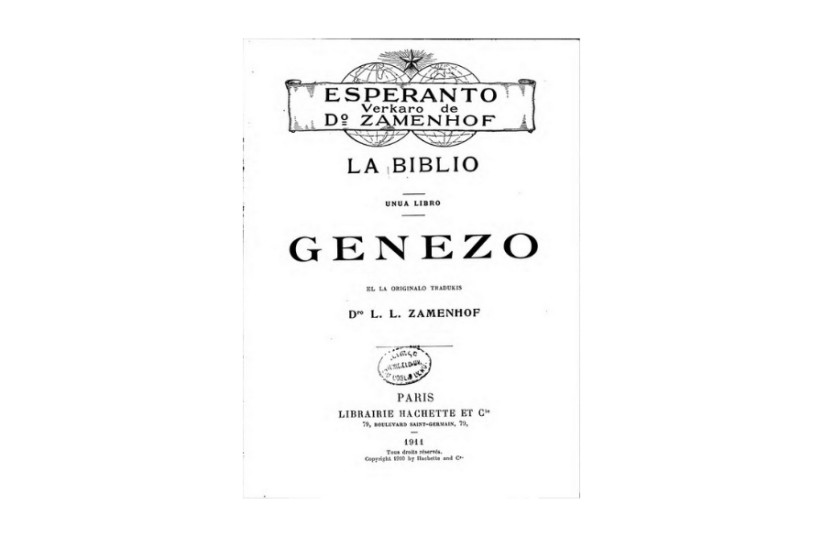

Doctor Hopeful’s linguistic Genesis

Zamenhof invented his new universal language twice. His father found and burnt the first manuscript when the youth was away in Moscow at university. We have but one poem in this precursor to Esperanto; its predictable theme, kindness, fraternity, and romantic striving. Esperantists thus have a small fragment of a proto-language, just enough to be certain that the later invention proceeded from it, as well as so little as to leave room for wondering speculation about what else there may have been in those early writings that were consigned to the flames and irrevocably lost. Esperanto as an invented language has no pre-existence, no antiquity ipso facto; so its creator’s first attempt is the subject of fascinated study, a bit like mystical speculation about the ages that preceded Genesis.

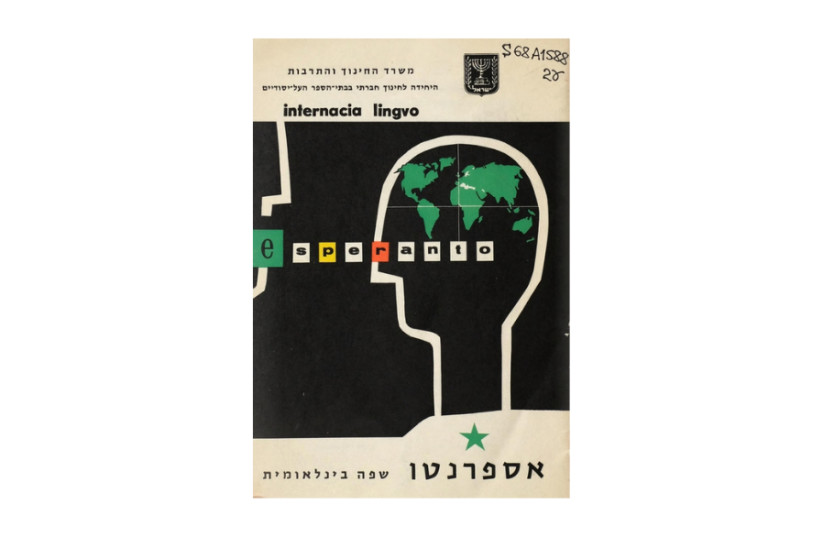

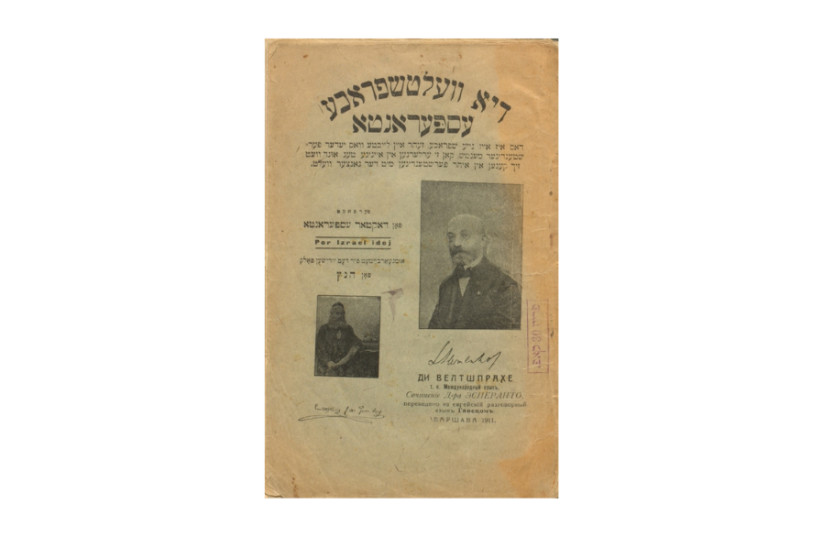

Zamenhof never actually gave a name to his new language, perhaps because names help to reify things, to create boundaries and exclusive identities – the very ills he wanted to avoid, transcend, and remedy. He termed his invention simply an “internacia lingvo” and, as we have seen, modestly employed as a nom de plume in his manual of the language the present participle singular “Esperanto“, which means in it “One who hopes”. As noted above, that first edition of the manual, La Unua Libro, was published in Russian, though translations into other languages swiftly followed – and indeed for the first two decades or so of the existence of Esperanto, about 90% of the movement’s subscribers and supporters were subjects of the Russian Empire. A majority of those were Jews as well, and though statistics are hard to come by, it might be fair to estimate that perhaps as much as a quarter of the present Esperantist community is Jewish.

Generations of Esperantists

The geographical trajectory of Zamenhof’s life matched the Diasporist aspect of his universalist convictions: he traveled within Europe to congresses, but never set foot in the Land of Israel. Indeed, he never lived permanently very far from his birthplace, spending much of his youth and all his adult life in the poverty-stricken Jewish neighborhood of Warsaw where his parents had moved the family in his boyhood. His oculist medical practice, in keeping with his humanitarian ideals, served the community while barely supporting his own family. He charged his patients the nominal sum of 20 kopeks a visit. Like Eliezer Ben Yehuda, the father of modern Hebrew, he received some financial aid from his father-in-law to augment the meager income with which he provided for his wife and three children. Much of the expense of printing and mailing Esperanto periodicals and other publications came out of his own pocket. The three Zamenhof children, Adam, Sofia, and Lidia, were devoted to their father’s cause, yet though Doctor Hopeful had placed his confidence in the lands of exile, his children paid the ultimate price for that decision.

The following September, the Germans destroyed the Zamenhof house and its priceless Esperanto archive in their terror bombing of the Polish capital. The family moved to an older home, within the area soon to be demarcated as the Warsaw Ghetto. Zamenhof’s son Adam was killed in prison by the Germans as a hostage in the early days of the occupation, and the Nazis murdered both daughters in the death camp at Treblinka later on, during the liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto in 1942. Their house was right next to the Umschlagplatz, the space into which the Jews were herded before boarding the trains for deportation, mainly to Treblinka.

The hymn of the Esperanto movement became and remains a poem Zamenhof composed, “La Espero” – “The Hope”. It is often sung ceremonially at Esperanto congresses and other gatherings, where Zamenhof’s rallying cry still echoes: “Let us labor and hope!” Some estimates optimistically place the number of people familiar to some degree with the language at nearly two million, and it is now among the languages taught on the popular website and app Duolingo. But there are only perhaps some ten thousand fully fluent speakers. There are also a small number of native speakers of Esperanto (known as “denaskoj” – “from-birth(er)s”) – people who learned it from parents who used both it and a native natural language at home. The Internet (“reto” in Esperanto) has enhanced Zamenhof’s vision of a linguistic community with a home in the noosphere, though the high ideals of Dr. Esperanto remain far from being realized.

Yet now, in the 21st century, what is it Esperantists are hoping for?

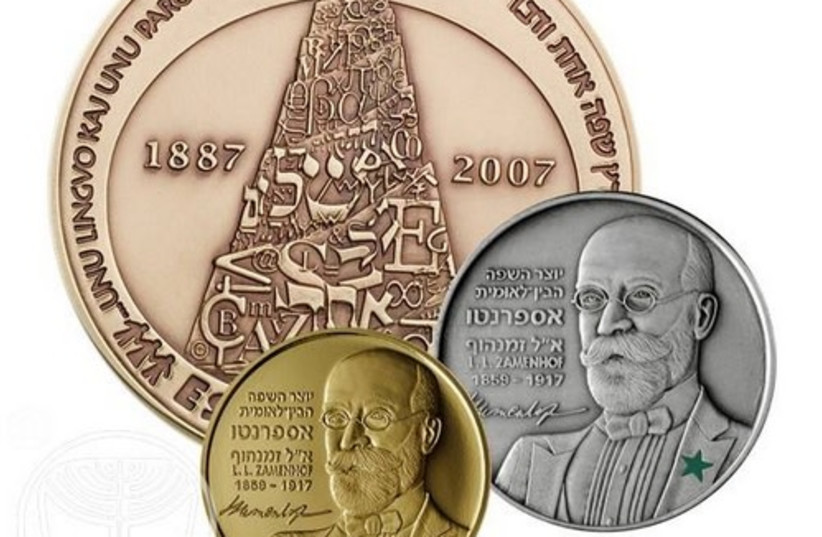

Legacy on a coin

In 2007, the Coins and Medals Corporation of the State of Israel struck a handsome medal in gold, silver, and bronze issues to commemorate the publication of Zamenhof’s book, La Unua Libro. It is a generous tribute by the victorious Zionist project, with its invented language, to an alternative vision, with its own language, that through no fault of its own did not attain its highest aspirations. I have the bronze medal, which is the largest in size of the series, before me as I write these lines describing it. It is a handsome object. The medal is a dignified tribute to a beloved son of the Jewish people, to his genius, his noble, self-sacrificing ideal and invention; the design breathes the artist’s respect and affection for his subject.

The medal’s reverse shows a stylized, ziggurat-like tower of Babel with an ascending spiral path leading up to the new reversed-and-joined-E symbol of the Esperanto movement, and along the rim is the Biblical verse partially in Esperanto and fully in Hebrew, “Va-yehi kol ha-arets safah aḥat u-devarim aḥadim/ Unu lingvo kaj unu parolmaniero” – “(And all the earth was of) one language and one manner of speech” (Genesis 11:1). At the base of the tower is the word “Esperanto” in Latin script, flanked by little male and female silhouettes holding hands. Letters of many languages, including Chinese, Greek, Sanskrit (Devanagari), Latin, and Russian, are worked in delicate relief on the surface of the tower. The Hebrew words for “One” and “peace” stand out, the latter echoed by the equivalent in Esperanto and Russian, as the emblem of Esperanto just above the tower’s summit attests to the nobility of human striving to resolve the disunity of Babel. Towards the top of the tower, delicate and faint, but unmistakable in its script and message, is the Hebrew word “hatikvah” – “hope”.

This article originally appeared on The Librarians, the official online publication of the National Library of Israel dedicated to Jewish, Israeli, and Middle Eastern history, heritage and culture.